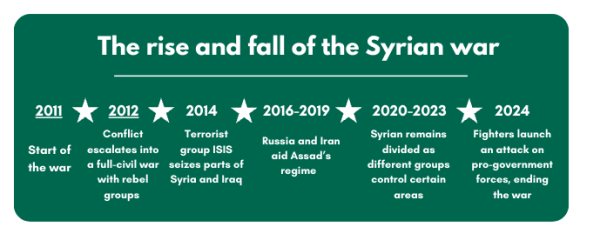

Fifty-four years ago in 1970, Hafez al-Assad’s, former president of Syria, seizure of power marked the grim beginning of a brutal half-century of oppression. After the leadership of Assad and then his son Bashar al-Assad, countless Syrians faced imprisonment, torture, displacement from their home and the suppression of their cultural and religious practices. Their livelihood was destroyed, and forced disappearances and executions tore their families apart.

This period of suffering, however, would not define the Syrian people’s future. Syria finally found a path to freedom.

While the journey was tough and people faced immense adversity and loss, the resilience of the Syrian people prevailed. Rebels pushed into each city starting from Aleppo on Nov. 29, 2024 and made their way into Damascus by Dec. 8, 2024, causing Bashar al-Assad to flee to Russia.

After decades of oppression, Syria is finally free.

“Given everything the country has been through, the war caused so much destruction,” senior Bashar Jabar said. “And freedom is important too, so it came at a high cost.”

What began as an attempt to reshape the country’s future under authoritarian rule spiraled into a relentless cycle of fear and control. This culminated into a civil war that would scar the nation for years.

Anti-regime protests started in the city of Daraa and spread throughout the country to big cities like Damascus, Hama and Homs. Initial protests happened because of the arrest of 15 boys in the town of Darra after painting graffiti slogans that said “It’s your turn, doctor” on a high school wall. These graffiti slogans directly challenged Bashar al-Assad, the former Syrian leader and ophthalmologist who was known for his authoritarian rule.

For over a month, the boys faced extreme torture. This went as far as one of the boys dying from infections in open wounds.

The graffiti sent a political idea suggesting that the Ba’athist party was next to fall after the Arab Spring revolutions. This was further complicated by Bashar al-Assad’s role as the secretary general of central command within the Ba’athist party.

When the war started, many citizens made the decision to flee the country with their families in search of safety. Syrians were spread out in neighboring countries such as Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon, trying to avoid the horrors that were happening in their country.

After years of war and displacement, Syrian students who fled their homeland are now watching from afar as Syria experiences a new chapter of freedom. For some, it’s a moment of hope. For others, it’s a bittersweet reminder of everything they left behind.

Jabar experienced the horrors of the war firsthand, living four years in Syria before his family was forced to seek refuge in Jordan. The memories of his homeland were blurry, but they still remain a significant part of Jabar’s identity.

“Even though I live in the U.S. now, Syria is a big part of who I am,” Jabar said. “Growing up in a Syrian household, surrounded by the language, the food, the traditions kept my connection to Syria life.”

Leaving behind their home, friends and everything they knew, the Jabar family embarked on a treacherous journey filled with uncertainty and fear, longing for a peaceful life that seemed so far out of reach. Despite the hardships, the Jabar family held onto hope, dreaming of a day when they could return to Syria free from conflict.

SHS graduate Mehiar Al Laban had a similar experience. However, being older, he was politically aware and even had an uncle who was a freedom fighter and a leader of a rebel group.

“My uncle was one of the leaders with the group, so he informed us to go and hide somewhere – they’re going to start bombarding the whole city,” Al Laban said.

He feels that people aren’t able to express themselves due to the controlling government back home. Al Laban celebrates his culture confidently and freely in the U.S.

“There isn’t a specific thing about Syrian culture that I can’t do here,” Al Laban said. “It’s a free country, so I can do more stuff here than in Syria.”

Syria remained destroyed, oppressed and unstable. But everything changed after Nov. 27, 2024, when a coalition of opposition fighters launched a major offensive attack against pro-government forces.

In less than two weeks everything took a turn. It just took 11 days for Assad’s government to crumble. The rebels rammed through the country freeing city by city. The government tried fighting back, but the

movement was strong.

The people celebrated this victory by taking Assad’s statues and replacing the old Syrian flag with the Syrian revolutionary flag.

Now, most finally feel safe outside.

After nearly half a decade of relentless conflict, the emotional and physical landscape was scarred. For those who survived the end of large-scale fighting, it brought indescribable relief, but it was mixed with grief and exhaustion. Millions were displaced, families torn apart and entire cities reduced to rubble. The shift from fear and despair to a fragile sense of stability was monumental for those who endured the hardships.

Shaimaa Alhelwany, a professor, remained in Syria throughout the war and witnessed the conflict’s devastating toll.

“100 thousand martyrs, hundreds of thousands of detainees, forcibly disappeared, wounded, millions of displaced people and refugees,” Alhelwany said in Arabic. “Dozens of cities and villages were almost completely destroyed. They gave their lives, their people, their homes. Freedom is expensive, but it was worth it.”

Despite the fact that these rebel groups were once against each other, they put their differences aside and came together to solve this one problem they all faced.

Syria’s culture, resilience and sense of identity have been tested like never before, forever changing its citizens. But now, Syria is learning to combat a different battle: rebuilding itself after the bloodshed.

“It’s difficult to celebrate without remembering the pain and loss,” Jabar said. “I hope that one day, it can heal and be rebuilt, but that’s going to take a long time.”