Running red

Educators across the state are concerned about their profession and its future

Educators and supporters of the Red for Ed movement gather around the Statehouse on Nov. 19 to protest Indiana’s education policies. Around 15,000 people registered to attended the rally.

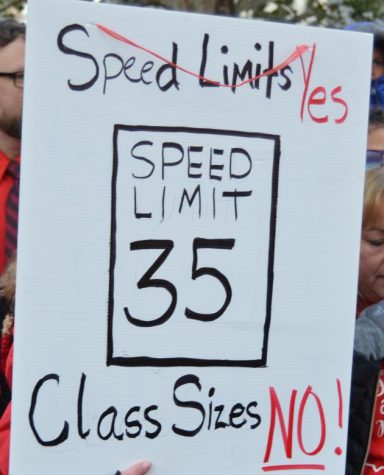

Educators from all around Indiana captured the attention of the state a month ago on Nov. 19. This caused over half of Indiana’s school districts to shut down. More than 15,000 educators protested outside of the statehouse for the Red for Ed rally.

“Red for Ed is more than a rally that lasts for one day,” Spanish teacher Conner McNeely said. “Re d for Ed is a movement sweeping across our nation saying that students’ needs matter, and what’s best for teachers is best for students.”

d for Ed is a movement sweeping across our nation saying that students’ needs matter, and what’s best for teachers is best for students.”

Similar to McNeely, many educators have expressed concerns for Indiana’s overall education system and how it will affect the future of the teaching profession. These concerns consist of a lack of education funding, lack of aspiring teachers and disagreeing with state education officials’ decisions.

Like the superintendents of many other school districts across the state, Crawfordsville Community Schools Superintendent Scott Bowling shut down his school district on the day of the Red for Ed rally, citing the fact that more teachers from Crawfordsville schools attended the rally than there were available substitute teachers to cover the positions. Bowling says he believes that his teachers wanted to participate in this rally to show that they felt disrespected by their state leaders. He says they feel like they put their all into teaching students every day, yet they aren’t given a proper voice within Indiana’s education system.

“Recently, the feedback that we’re getting, especially from the people that have power in our state, specifically state legislatures, is that we are not doing a good job and that there are better alternatives out there,” Bowling said.

German teacher Christopher Sponsler attended the Red for Ed Rally and he is also concerned about how state officials are treating public schools, especially financially. According to Sponsler, he believes that they are dedicating less money towards public schools and education programs in general, but he feels lucky to be in a township that isn’t suffering as others have suffered.

Math teacher Jason Adler agrees that the Perry Township district offers a healthy financial package, when pay and other benefits are taken into account. So he found that the best way for him to advocate for the students was to be for them at school instead of attending the Red for Ed rally.

Math teacher Jason Adler agrees that the Perry Township district offers a healthy financial package, when pay and other benefits are taken into account. So he found that the best way for him to advocate for the students was to be for them at school instead of attending the Red for Ed rally.

Students support their teachers by protesting at the Red for Ed rally on Nov. 19. Around 40 SHS teachers attended the rally that day.

“This is my vocation, my call to serve, so I’m here for the students in the classroom,” Adler said. “I understand those who thought the best way to advocate for the students was by going to the statehouse.”

Math teacher Jack Williams also feels that Perry Township has a strong system and respects those who are speaking up about their concerns for teachers. He says there are many issues that have been voiced, but he is hoping that some of the educators who attended the rally will make their concerns more clear and precise.

“While I have no problem with educators seeking more appreciation, more funding and more recognition, I would also like to see some educators define more clearly exactly what they want,” Williams wrote in an email to The Journal.

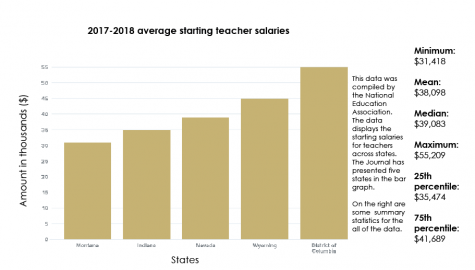

McNeely has been a strong supporter of the Red for Ed movement. He attended one of their rallies back in March and spoke in front of 2,000 people. McNeely believes that teacher compensation is a big part of Red for Ed. Many teachers around Indiana are frustrated because they put their time and energy into educating kids but feel that they are compensated with a comparatively low amount of money. He says if schools want to attract qualified teachers, then they need to be compensated as professionals.

Time plays a big role in Principal Brian Knight’s concerns. He says that state legislature should be aware of the restraints they put upon teachers and how it affects their teaching and the students’ learning. He believes that state legislatures are giving educators a lot of criteria to teach, but not enough time.

“We have to be cautious of the restraints we put on schools and teachers and the amount we are requiring them to do,” Knight said. “There’s only so many hours in the day and so much to accomplish.”

English teacher Julie Breeden stands with those who have financial concerns. Breeden is a union representative for SHS, which means teachers from the building can come to her with questions or concerns. It’s her responsibility to represent the teachers. She feels that there aren’t enough incoming teachers, and a lot of it depends on salary. Breeden says that the salary for a first year teacher is considerably lower than any other field, and it’s hard for teachers to feel respected when they aren’t compensated well.

However, Breeden thinks that the community will support and change Indiana’s education system for the better. She believes that Indiana is a place for families, and the majority of families want to put their kids in a good education system, so she is hopeful that the state will support education and make this happen.

As these issues surface, Indiana faces a teacher shortage. Fewer people are going to college to become teachers, and many schools in Indiana are struggling to find applicants to fill teaching positions. According to LearningPolicyInstitute, teacher shortages affect different subjects and student populations differently, and it all depends on multiple factors.

Bowling says he has seen a decrease of teacher applicants in the Crawfordsville district. In previous years, he got four to five high school teacher applicants, and now he’ll receive one, two or sometimes none. Bowling worries that this shortage will continue.

“We haven’t gotten people to apply, and it’s getting really scary,” Bowling said.

Breeden thinks that the image of being an educator has changed throughout the years. She believes educators have mostly consisted of women throughout history. Women would often get teaching jobs to provide a second income for their families, but now it serves as a primary income. A change is what Breeden believes needs to happen, and it would help if state legislatures supported it too.

“A real shift in thinking about education needs to happen on the level of state legislatures, and for many years teaching has been seen as a second income job,” Breeden said. “I don’t think that’s the whole problem, but it’s the heart of it.”

On the other hand, Dan Melnick, Associate Director of the Professional Community Programs at Indiana University, has high hopes for the future of Indiana’s education system. He works in the career connections department and they help students find jobs after college. Every year, Melnick says IU surveys graduates from their education program and data shows that 93% of the candidates get a teaching position right off the bat.

Along with high hopes for the future, Bowling believes that more creativity and flexibility should make its way back into the classrooms. He feels that nowadays teachers only have a short amount of time to teach a subject, and kids are beginning to rely on tests as their only output of knowledge. There is less time made available for projects, exploration and interpretation.

The future of Indiana’s education system is unknown, but educators like those at SHS are hope changes will be made to benefit their profession and their students.

“We tend to take for granted that this huge institution of public education will always be there, in all of our memories it always has been,” Breeden said.