In the dynamic landscape of education, where the infusion of artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping traditional teaching methods, English department co-chair Sam Hanley has found himself at the forefront of a heated debate. Recently, as Hanley meticulously graded essays, he made a disconcerting discovery that students were utilizing AI to compose their assignments.

The revelation stirred a wave of anger among both educators and students, prompting Hanley to contemplate the implications of this technological reliance on foundational skills. In response to this growing trend, Hanley voiced a poignant concern that resonates far beyond the confines of his own classroom.

“Did the person who wrote these AI things … have to hand write their essays when they were in high school? Did they have to write from scratch,” Hanley said. “Because I bet they did, and they learned something from doing that that we’re going to lose if we’re not careful.”

It’s no secret that AI is here at SHS and even in the first few paragraphs of this story, which were written completely by ChatGPT. Despite AI’s presence, there is no school or township policy to dictate its use, which some believe is due to its swift rise. Though many people have concerns about AI’s potential negative effects on the learning process, others point to its capability to revolutionize education.

With its roots in the 1950s, AI is not a new concept. The past few years, however, have dramatically increased its availability and capabilities.

Microsoft, for example, recently overcame Apple to become the most valuable company at over $3 trillion because it quickly embraced the shift to AI, according to an article in The Washington Post.

In simple terms, AI is any technology that models human intelligence. Fed with vast amounts of data, it then finds patterns to base its decisions off of.

“It approximates how a human might make a decision, or what decision we would make, but (in ways) we couldn’t really understand,” said Danny Sallis, a junior at Stanford who is studying computer science and has taken several classes on AI.

The exponential growth of AI and increase information input, and the constantly expanding online web provides just that.

As seen with ChatGPT, this data increase has proven itself wildly successful in upgrading AI, which is now able to generate complete ideas, paragraphs and even essays based off of a single question.

This upgrade, however, comes with its own host of questions.

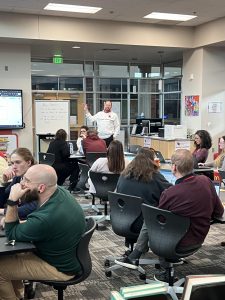

Effect on teaching

Some people view AI as the future of education: more personalized instruction for students, less burden on teachers and innovation all around.

At SHS, English teacher Jessica Lyons uses AI in her classroom to help level instruction. When giving tests, she uses ChatGPT to rewrite a base reading passage and comprehension questions at different levels to give each student a personalized assessment.

Along with leveling tests, Lyons uses AI for peer reviews. Students aren’t always able to give the best feedback on essays, according to Lyons. AI, on the other hand, gives students specific suggestions and can then help them work through making changes to their essays.

Lyons “function(s) under the idea” that students doing work outside her class are probably using AI, and she believes they should be allowed to do so as long as they go back to add in their own voice.

“(Students) might (use AI), and I don’t have a problem with them doing that if then we go through and we edit and we review,” Lyons said.

Even though Lyons has used AI with her students and believes in the importance of teaching kids how to use it responsibly, she thinks it has a bigger potential to be an assistant for teachers.

“I see it more as a tool for teachers,” Lyons said. “But I also realize kids use it, and I think it’s just one of those things that’s our responsibility to explain to them how to use it.”

Outside of SHS, Lyons has done over 20 presentations at education conferences about ChatGPT and how it can help teachers reduce their workload and enhance their lessons according to her blog, “The WriteWay with Lyons.”

SHS principal Amy Boone believes AI resources that help with lesson planning could allow teachers to be more efficient, thus freeing up additional time for them to give students feedback.

Perry Township Superintendent Dr. Patrick Spray agrees that there are possible upsides to AI, but he also thinks that Perry Township needs to explore these technologies more in order to ensure they are used responsibly. This is why the township has yet to create a policy for AI use. Spray says they plan to wait for guidance from the Indiana School Boards Association to do so.

“I think there are definitely some opportunities out there to leverage it and leverage it well,” Spray said. “But also I think that we need to learn more so that we can help not only our staff but our students be good consumers of it.”

Despite the potential benefits of AI, there are still many people who worry about what it could mean for the future of education.

A major debate on AI is whether it is taking advantage of available resources or plagiarism.

To Hanley and fellow English teacher Dawn Fowerbaugh, the answer is clear: Using AI is plagiarism. When students use AI, according to Hanley, they aren’t actually processing any information or doing any critical thinking.

“If all I have to do is … give the right question to AI and I get something that is autogenerated, that’s taking the thinking out of it entirely,” Hanley said, “and that’s terrifying to me.”

Given that Hanley and Fowerbaugh view AI as plagiarism, they treat it as such. Any plagiarism, whether it is copied from the internet, from another student or from an AI source, is handled as a disciplinary offense.

What makes AI more difficult to deal with than other methods of plagiarism, teachers can use online tools to search for stolen material, but because AI is constantly drawing from more and more sources, its responses aren’t static, thus making it challenging to detect.

What makes AI more difficult to deal with than other methods of plagiarism, teachers can use online tools to search for stolen material, but because AI is constantly drawing from more and more sources, its responses aren’t static, thus making it challenging to detect.

“I’m sure I catch some kids, and some kids do just enough or change it just enough that it’s hard to catch them,” Fowerbaugh said.

Online AI detection tools do exist, but they aren’t very sophisticated, which leaves teachers to make the ultimate judgment on whether students are using AI or not. There are some signs that give away AI writing, according to Hanley, such as the tone and sophistication as well as the general formulaic structure of AI generated essays.

Although teachers can use these clues to identify AI work, this still puts excess stress on them.

“I literally will spend an hour and a half on one kid’s essay that cheated just so I can back myself up,” Fowerbaugh said.

This time drain has pushed Hanley and Fowerbaugh to consider switching their AP Language classes to paper and pencil writing to help eliminate the possibility of AI produced work and allow them to see their students’ true writing levels.

However, the digital push from College Board, the organization which runs AP testing, makes this solution difficult.

“One thing working against us … (is that) starting in 2025, most paper and pen AP tests are going to computer,” Hanley said.

Keeping the potential positives and negatives of AI in mind, the most important thing to consider going forward for Boone is balance.

“It is a tool, and it’s something that isn’t going to go away and that I want to make sure students know how to use appropriately,” Boone said. “It depends on each situation what would be considered appropriate.”

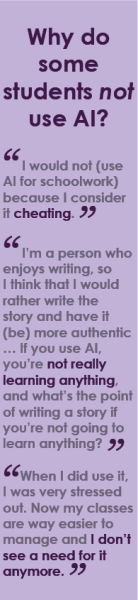

Effect on students

Teachers and students agree that part of the reason students use AI tools is because of stress. When students have too many things on their plate and feel pressured to complete assignments, some will turn to AI as an easy out.

“I was going through a period of time where I could not get any work done because I was doing a bunch of medication changes,” an anonymous student said.

This student struggles to find the momentum to start essays and sees AI as a stepping stone to then edit and make it their own. They don’t believe it is cheating or that they will face any negative consequences because they incorporate their own ideas into the AI generated ones.

“I’m still doing the thought process,” they said. “I’m still working through it.”

For this student, the fact that people need to use AI in order to complete their assignments highlights a bigger problem in education.

Another anonymous student uses AI tools for dual purposes.

At times, they will use it to help explain the process behind a confusing topic in one of their classes, which they consider to be using a resource, but they also use it to copy answers at times, which they consider cheating.

“If I really want the help, then I’ll use the AI to get the answer, but I also read the explanations and help myself by reading them,” they said. “But if there’s times where I really just don’t want to read them, I’ll just use the answers. That’s it.”

This student has felt the negative effects that AI brings firsthand.

“I sometimes rely on the AI,” they said, “so when tests come up … , it’s confusing, and I don’t really get it.”

A final student heeds a strong warning. After using the technology on an essay last year, guilt quickly set in, leading them to confess to their teacher.

At the time, they had many difficult classes, were overstressed and saw AI as a solution. Today though, they consider AI cheating and haven’t used it since. In their opinion, it completely takes away a student’s ability to learn.

Going forward, this student has vowed to never use AI on an assignment again, citing a “guilty conscience.”

Even though they will never use it again, they know plenty who will. Many people who they know use AI for every assignment, no matter the class, and have yet to be caught. According to this student, teachers’ methods to catch AI “don’t seem to be working.”

Beyond SHS

Some proponents of AI in schools point out that students will need to use it later on. While this is true in some fields, it isn’t a universal statement.

According to Dan Spehler, a Fox59 and CBS4 news anchor, all of the reporting done at the studios where he works is original. One main flaw of AI is its inability to convey the human side of stories. While it may be able to piece together thoughts that form a story, it will lack the emotional factor that comes with human-created work.

“It just doesn’t understand the complexity or the actual human story behind whatever it just tried to write about,” Spehler said.

On the other hand, some fields are embracing AI. At Stanford, for example, there are new classes on how to use AI tools for computer coding, classes that explore the theory behind AI and classes where professors are open to students incorporating it into their projects.

“If you wanted to use (AI) you could, as long as you cited it as a source,” Sallis said.

More than anything, AI poses a huge question. With its ever-expanding knowledge base, there’s no limit to what it may be capable of one day. AI’s capacity to continually grow is what many people fear, according to Boone and Spray.

This uncertainty has pushed some to question whether it is better to continue charging forward with AI technology or slow down to be more intentional with its development.

“Big companies (are) saying ‘pump the brakes,’” Spray said. “We don’t know what the power of this is, and do we really want to go as fast as we can to unlock what could be Pandora’s box?”

Whatever the future of AI may look like, one thing is certain. Teachers like Hanley will continue to fight for critical thinking and individual ideas, no matter what.

“We have to think. We have to learn,” Hanley said. “We have to understand that you know what, (learning is) hard and messy, and if it’s too easy, we’re probably not learning anything.”