A hand gripped her neck and led her into the hallway.

Her face slammed into the wall, and she was lifted off the ground. Fear took over her body as she realized what was about to happen.

The sound of the snap of a belt and yelling filled her ears.

Seventeen-year-old Joan Tejchma only had one thought as her father beat her legs with a belt: stay still, or else it’ll get worse.

This left more than a physical mark on Tejchma. The memory left a mental scar that stayed with her as an adult.

Throughout her childhood, Tejchma survived abuse, gang violence, racism and poverty. As each day went on, she never knew if there’d be a next.

Tejchma grew up in Northwest Indiana, an area known as the Region. Within the Region, she lived in Gary and Hammond. According to Indy’s Mobile News, Gary is ranked the second most dangerous city in Indiana.

This environment forced her to become independent, and she carried her self-reliant mindset outside of the Region.

“I never got any sympathy from anyone, and that makes you hard to the world,” Tejchma said. “Once you leave here, besides your family, no one cares. You need to understand that life is hard.”

“I never got any sympathy from anyone, and that makes you hard to the world,” Tejchma said. “Once you leave here, besides your family, no one cares. You need to understand that life is hard.”

During her childhood, Tejchma’s environment brought out the survival instinct in her. Her earliest experience of abuse was inside her own home.

From the age of 3, she had to endure physical abuse from her father.

For Tejchma, there was no time-out. Her father, who was an Marine, had harsh disciplinary measures for his children.

The thought of going home terrified her.

“You couldn’t talk back to him,” Tejchma said. “We couldn’t voice how we felt.”

She was scared to death of her father. She didn’t know if she’d ever make it past 18 years old because she thought her dad would have killed her.

The sound of his footsteps brought her fear.

“I was always scared … ,” Tejchma said. “I did everything possible not to go home.”

But above the abuse was her mother, Sylvia Myers.

Tejchma’s parents were divorced until they got back together when she was a teenager. During that time, her mom and dad shared legal there wasn’t much her mother could do to prevent the abuse.

“My mom said he liked us until we could talk,” Tejchma said. “We would just run to her, and she would hang onto us, but he would just yank us away.”

While living with her father was scary for Tejchma, life with her mom was different.

While living with her father was scary for Tejchma, life with her mom was different.

She felt safe with her mom, and her presence itself was a comfort. She says her mom was always very loving and supportive, and her fondest memories took place with her.

“She’s great, (and) she’s my rock,” Tejchma said. “She was always there for me, and I felt safe. I remember we used to snuggle on the couch and used to watch old scary black-and-white movies.”

While living in poverty, Tejchma says her mom always tried her best for their family.

Her family moved back and forth to find less expensive housing, and they always tried to find a cheaper place to live. Myers wasn’t aware of subsidized housing and food stamps that were available to her.

“We didn’t have furniture,” Tejchma said. “We had one bed, and all the other rooms were empty. We didn’t have a refrigerator, so we used a coo

ler for our food, and we didn’t have an oven, so we used a hot plate. I remember powdered milk is disgusting. I just remember being cold.”

Despite her family not having much, Tejchma’s mom always tried her best to make sure they had food and heat.

“It was tough, but I think a lot of people have it tough sometimes,” Myers said. “We seemed to survive it. Just knowing that you’re there for each other and if things get worse, (you’re) able to go through it. We had a lot of faith.”

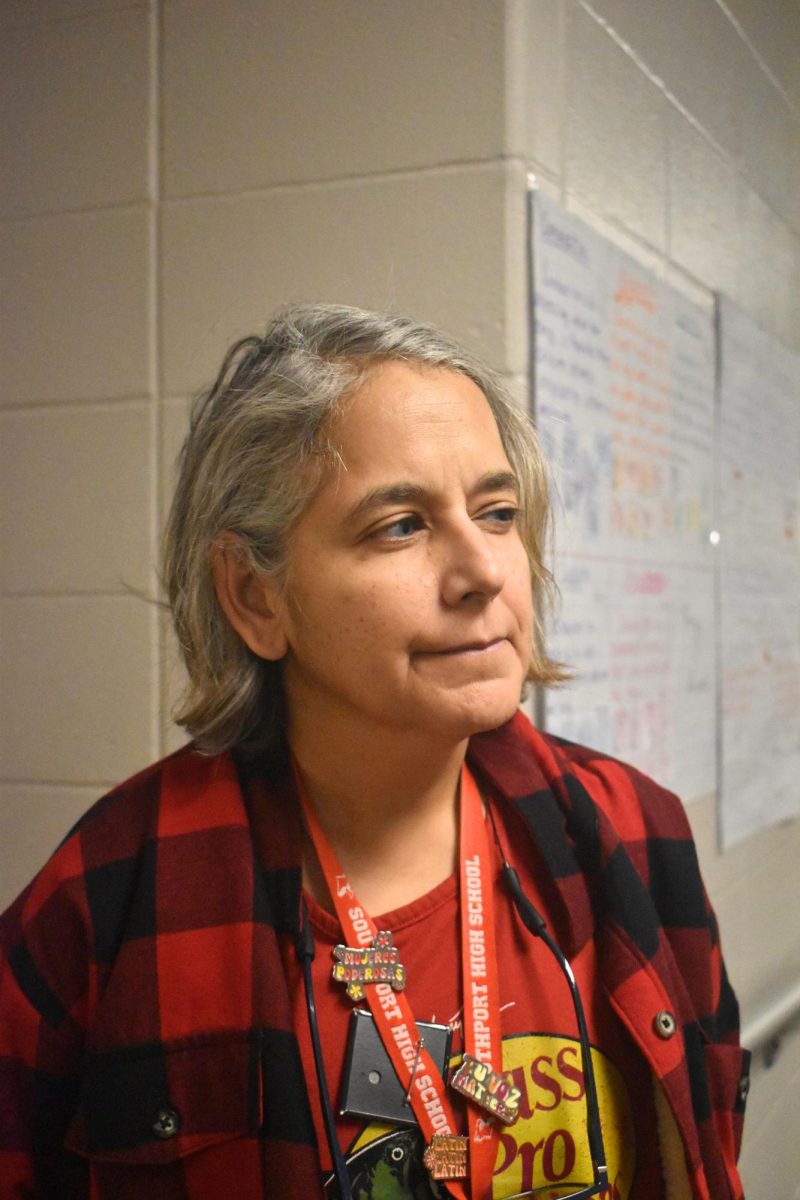

photo contributed by Joan Tejchma

Tejchma says, at the time, she didn’t realize she had nothing because no one around her did either.

The poverty also caused her to jump from school to school. Since she moved homes constantly, she went through 10 different elementary schools in the course of five years. During the school adjustments, she encountered racism from one of her teachers.

In the third grade, she was unfairly targeted because of her ethnicity. As a young Latina, she was facing prejudice as a minority in the classroom.

“(The teacher) would display everyone else’s A’s, and she would hang them up, put stars on them, and I had A papers, but she wouldn’t hang mine up,” Tejchma said. “She would be sure not to look at me when she was talking to me, and she was always just kind of cruel.”

At the time, Tejchma says she was aware of the racism because she also saw the way her mom was similarly treated.

She watched as people deliberately ignored her mom.

“I remember people walking out of their way so they wouldn’t have to get close to her. . . ,” Tejchma said. “They wouldn’t look at her.”

She says the similar treatment from her teacher made her bitter, and it pushed her to want to become better.

While she faced negativity in elementary school, Tejchma’s high school was a home away from home for her. She was able to form strong friendships that later became her support systems. She was able to find the diversity she missed in elementary school.

She cherished the close connection with her friends, but she felt a shift in their friendships later in her life.

Tejchma was forced to break off her friendships as soon as her friends joined a gang. She watched them pick a different path in life, but she knew that route wasn’t for her.

“(We were close) before they went into gangs but not after,” Tejchma said. “You had to be distanced. You had no choice.”

Tejchma avoided gang involvement at all costs, which helped her survive. After she heard the requirements to join, she automatically declined.

To be a part of the group, she says, the initiation required undergoing rape five times. She didn’t want to go through the trauma and violations that the gang forced upon the members.

Not everyone survived. Within two years of joining, some of her friends died due to the violence.

She still remembers her friends who didn’t survive, even 35 years later.

“That seems kind of unreal when you’re young,” Tejchma said. “When someone you know passes away, you don’t understand why the world doesn’t stop for that. The world just keeps going, and that was the hardest part.”

After these experiences, it wasn’t just her friendships that changed. The grief made Tejchma a more sentimental person. With all of her friends today, she says she always holds on as tight as she can.

This even includes her current friendship at SHS with colleague Lishawna Taylor. They’ve been friends for almost a year, and Taylor says their friendship has become something she can count on.

“(Our friendship is) having somebody that I can talk to, and someone I can lean on, because it’s not easy to do what we’re doing by ourselves. . . ,” Taylor said. “We are double strong because we’re together.”

In the past, to distract herself from the sadness, Tejchma would constantly stay busy. High school was an outlet and a distraction for her.

“I’d do school, sports (or) activities,” Tejchma said. “I would be at school until 7 at night.”

During school, she loved her chemistry class. Not only did she enjoy the subject, she also enjoyed her teacher.

He always pushed her to be better at chemistry, and she’s never forgotten him.

“He told my mom I had a knack for it,” Tejchma said. “And that early on sticks with you.”

While her chemistry teacher’s impact was important, it wasn’t the only defining factor. At 18, Tejchma received a full scholarship to IU for journalism.

As soon as she got her scholarship, she knew she was on her way out. “I got my scholarship acceptance letter,” Tejchma said. “My chemistry teacher was so proud of me, and he made like 20 copies of it.”

She says that moment defined her independence, and she realized she was on her own.

Her mom beamed with pride when she was told the news.

“I was really proud of her … ,” Myers said. “The thing is, now, she’s so successful, and she pretty much has done it on her own.”

In August of 1989, she began to pack for college. As she was in her house, preparing to leave, her father approached her.

“When I got the full scholarship and we were packing my stuff to go to IU, instead of him saying he was proud of me, he said, ‘You think you’re better than I am, don’t you?’” Tejchma said. “I was like, ‘Yeah, totally.’”

After the conversation, Tejchma walked out. Her uncle drove her to IU, and it was from there that she unpacked her future.